art | language & land

A Mythical Country (State Library of NSW)

2018

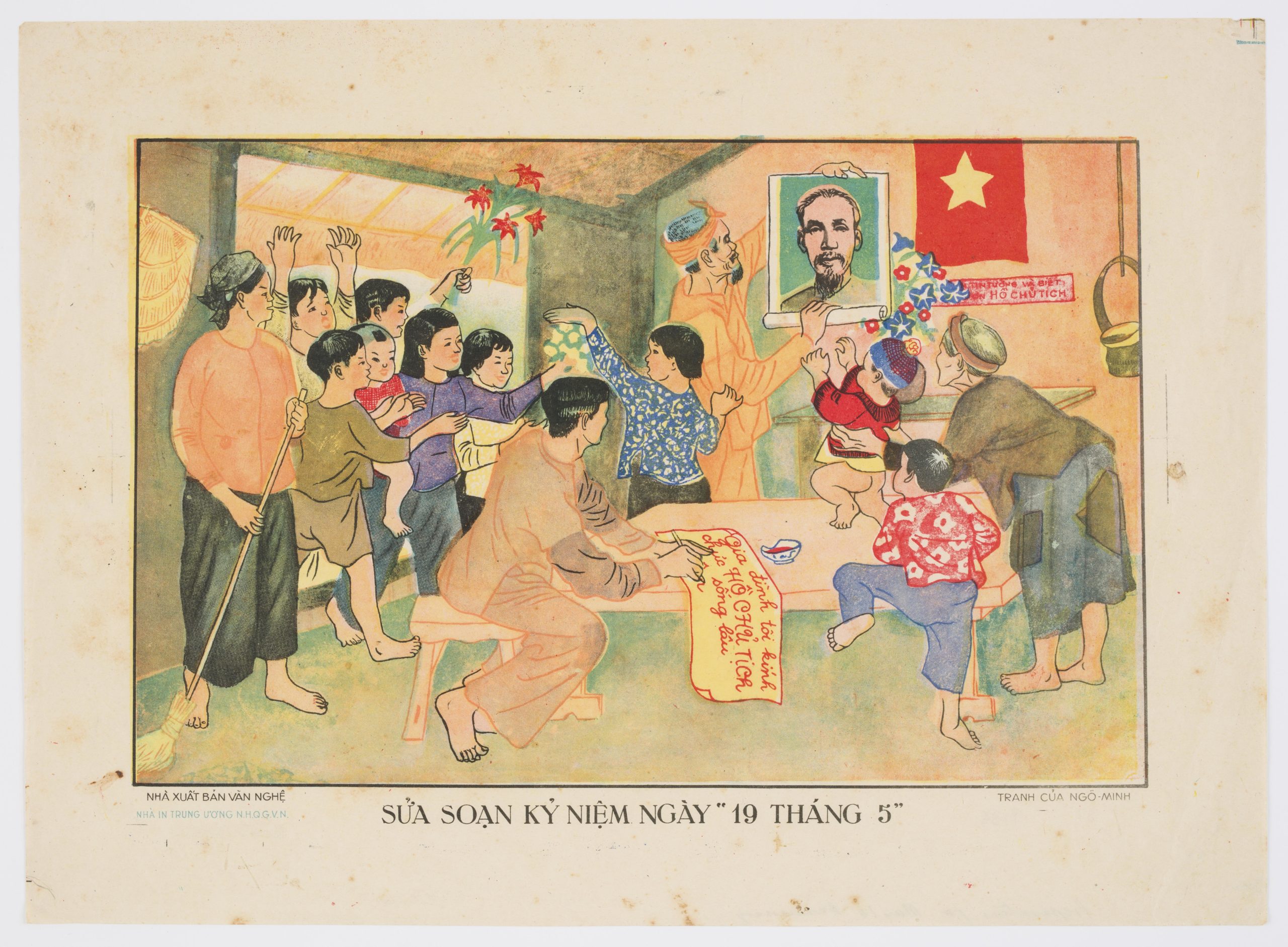

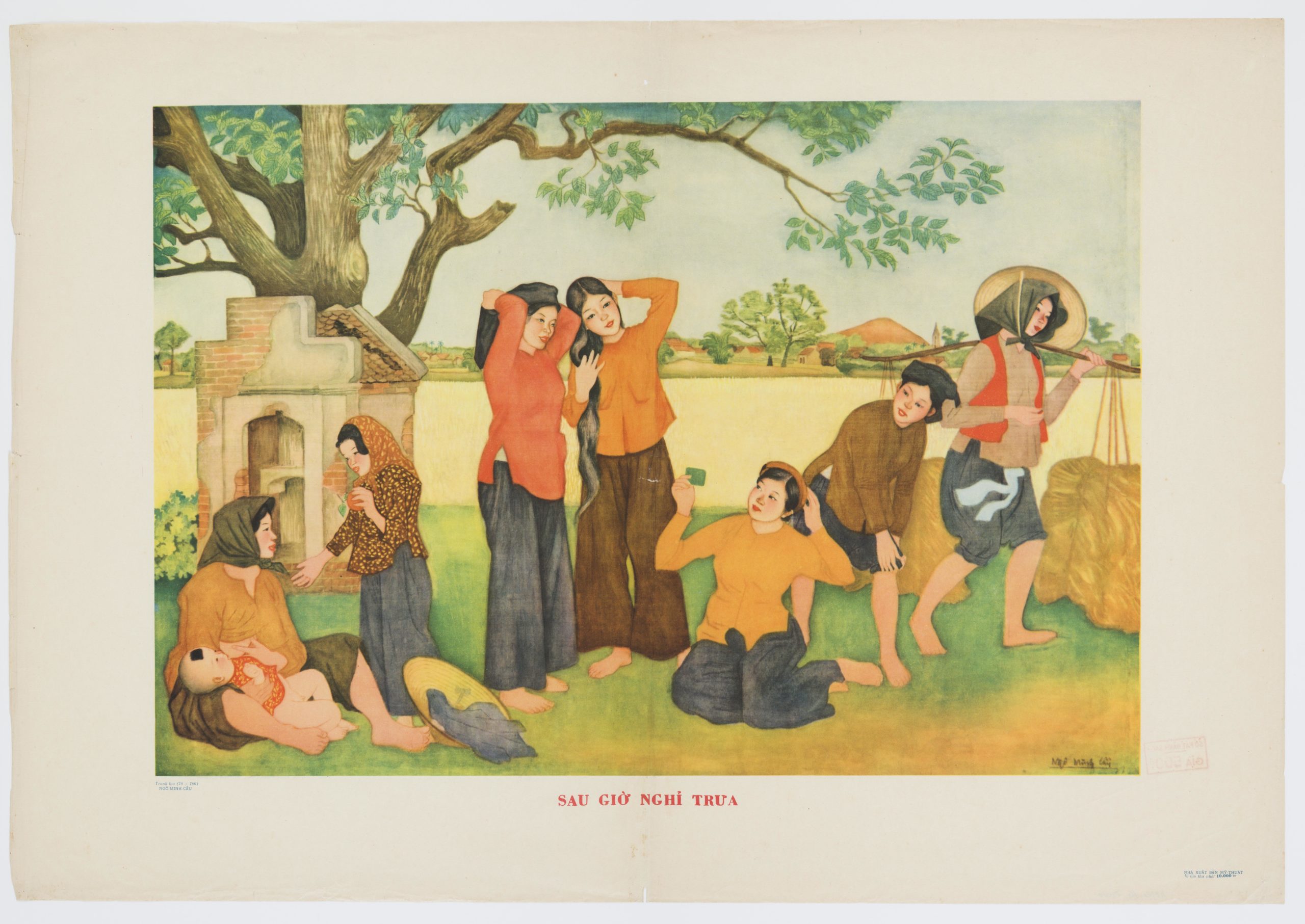

During 2018 I was commissioned to undertake research for a feature article for the State Library of NSW’s magazine. It sent me on a fascinating and unexpected path examining a large collection of Vietnamese poster art from the 1950s that the library currently holds in its special collection. Following on from my article which was published earlier this year, I’m now working with the library’s curatorial team to display a small exhibition of the posters for the Library’s Amaze gallery for December 2019 – April 2020.

Full text

Mythical Country

In 1956, Australian writers Mona Brand and Len Fox boarded a cargo ship from Melbourne to Rangoon en route to Vietnam.

Though newly married, this was not their honeymoon; they were making their way to Hanoi to take up two postings with the North Vietnamese government to help its employees and others improve their English. Their friend Wilfred Burchett, a notable Australian journalist, had recommended them for the roles.

When Brand and Fox made up their minds to go, they had little idea of what to expect. Two years later, they found leaving ‘an emotional wrench’. ‘As the train left the station and the haunting sounds of one of our favourite lullabies filled the air, we both broke down,’ recalled Brand in her autobiography, Enough Blue Sky (1995).

Alongside their day-to-day work in Vietnam, the couple wrote and published several books, including Fox’s Chung of Vietnam (1957) and Friendly Vietnam (1958), and Brand’s Daughters of Vietnam (1958). The Library holds these books, the last two as part of the Dame Mary Gilmore collection. However, the Library has an even more astonishing legacy of Brand and Fox’s time in Hanoi: their enormous trove of Vietnamese art.

This collection largely comprises art posters and other ephemera. Most were commercially printed and sold cheaply, and these works were presumably much admired by Brand and Fox, as there are yellowed marks visible on the corners of many of the pictures from having once been taped to their walls.

Back in the 1950s, what did Australians know of Vietnam? This was the time, of course, before the country was thrust onto the world’s stage in the 1960s and 70s. Perhaps many of Fox’s contemporaries could relate to what he wrote in Friendly Vietnam: ‘Vietnam has always seemed to be a mythical country, a land that you hear about but do not visit.’

Posters and artworks from Vietnam (Hanoi), 1952–61, collected by Len Fox and Mona Brand

In a way, I relate to this as well. For the first part of my life, Vietnam was a country I would often hear about but did not visit — until I was almost 30 and finally made my way there for the first time. But Vietnam wasn’t a myth so much as the place where my family’s story began.

Given the turbulent events that eventually led us to a new life in Sydney, I began my research into these artworks with some discomfort. After all, Brand and Fox were active members of the Communist Party of Australia, and moved to Hanoi to support the newly formed government of North Vietnam under the leadership of Hồ Chí Minh. My parents, on the other hand, were born and raised in South Vietnam, and became staunch anti-Communists. But where possible I strive to overcome such stark ideological divides, guided by my own sense of curiosity and a desire for connection, which often leads to unexpected rewards.

For one thing, stumbling across these miraculously preserved works has allowed me to reach back into Vietnamese history in a way I hadn’t known was possible here in Sydney. Also, the more I read of Brand and Fox’s writing, the greater the sense of kinship I’ve felt. It’s clear they were sincere anti-war intellectuals who took great delight in learning about Vietnamese culture and history beyond the topical concerns of colonialism and war. Without much by way of Vietnamese language, their interactions and observations are impressive. Being activists for Aboriginal rights in Australia, it’s not surprising that they were both keenly interested in Vietnam’s many ethnic minorities; in the collection are several beautiful sketches of Hmong women.

Brand and Fox did not venture below the 17th parallel that separated North and South Vietnam during their time in Hanoi, and they viewed the regime of South Vietnam with immense skepticism. Yet, even though they ostensibly supported ‘the other side’, it is inspiring to read how intrepid they were, going off to live in Vietnam at a time when few Australians knew anything at all about the country.

Many works in the collection are by contemporary artists. Some had been trained in Western art traditions and had begun contributing to a modern style of Vietnamese art. But what I’ve found most fascinating are the examples of folk art. These popular artworks were produced — and continue to be produced — by artisans from Hanoi and surrounding villages. One set of woodcut paintings depicting tigers came from the Hàng Trô'ng and Hàng Nón streets of Old Hanoi, where Brand and Fox would have often walked.

There are also several examples of Đông Hồ folk woodcut painting, produced by a village in Bắc Ninh province, not far from Hanoi. These charming illustrations feature chickens, pigs, frogs, fish and other animals, all symbols of good wishes such as abundance, prosperity and honour. Many of these posters would have been used as decorations to celebrate the arrival of Tết, as the lunar new year was — and still is — the most important event on the Vietnamese calendar.

The colours in Vietnamese folk art were traditionally derived from natural sources, and the origins of the pigments described in Vietnamese Folk Paintings (2012) read like poetry:

The black was produced from bead-tree charcoal or ash from burnt bamboo leaves or straw. Verdigris was used for the blue. Red or yellow colours were created from Flamboyant or Royal Poinciana (Delonix regia) tree. A deep red colour was sourced from powdered red stone.

Looking at the collection, I’m reminded of how much Vietnam is a part of the Sinosphere, which is hardly surprising given the thousand years of Chinese colonisation. Among the mythological, religious and historical stories depicted in the artworks are great figures from Chinese history such as Trương Phi (Zhang Fei/張飛) and Triệu Tử Long (Zhao Yun/趙雲). My father would refer to these legendary military generals from the second and third centuries.

Posters and artworks from Vietnam (Hanoi), 1952–61, collected by Len Fox and Mona Brand

The country that Brand and Fox encountered, however, was not necessarily a nation mired in the deep past. Having ousted the French colonial forces, it was looking towards the future. In the collection are many examples of propaganda art, emotive works aimed at rallying people behind Communism and President Hồ Chí Minh. In Brand’s autobiography, she recalled the deep admiration she felt on meeting the president for the first time.

He greeted us warmly in English, asking if, being Australians, we found the weather too cold.

Posters and artworks from Vietnam (Hanoi), 1952–61, collected by Len Fox and Mona Brand

As compelling as these artworks are to me, the truth is I can’t help feeling an enormous sense of loss when I look at them. They are a reminder of the intangible gulf between Vietnam and Australia for someone like me. That grief is why I also felt particularly moved when I read Fox’s plea in Friendly Vietnam:

Is it too much to hope that since our countries have been brought close together by the advance of science, our people may come closer too — Australian mothers talking with Vietnamese mothers, Australian poets with Vietnamese poets, Australian music lovers with Vietnamese music lovers …?

Fox’s simple wish for Australia to become closer to Vietnam would come to pass; but he could not have predicted what else would occur after he asked that question more than 60 years ago. Back then, it was perhaps just beyond the imaginable that someone like me would one day be able to inhabit both of these identities — Australian and Vietnamese — at the same time.

Posters and artworks from Vietnam (Hanoi), 1952–61, collected by Len Fox and Mona Brand

Similar Projects

An Elite Education (Sydney Review of Books)

For one thing, I was not surprised that the man holding the highest office in Australia had asked me the same old tired question I’d heard a hundred times before.

The whole animal (Overland)

Now, more than ever, we need to reckon with our relationship with food and our consumption of non-native fauna.

Western Sydney is dead, long live Western Sydney! (SRB x UTP)

It doesn’t surprise me when I see the children of non-white migrants claim the identity of being from Western Sydney; if they grew up in a suburb with some notoriety then all the better.

Five common myths about raising bilingual children (SBS)

In our research for My Bilingual Family, a new podcast series from SBS, we met a number of bilingual families struggling with language in different ways.

A tale of two Michaels (The Guardian Australia)

Empathy is useless if it’s of the ‘thoughts and prayers’ variety. As Covid takes hold, south-western Sydney needs vaccines

Sydney lockdown: if we’re all in this together, let’s ditch the scapegoating (The Guardian)

There is a moral cost to doing the greatest good for the greatest number.

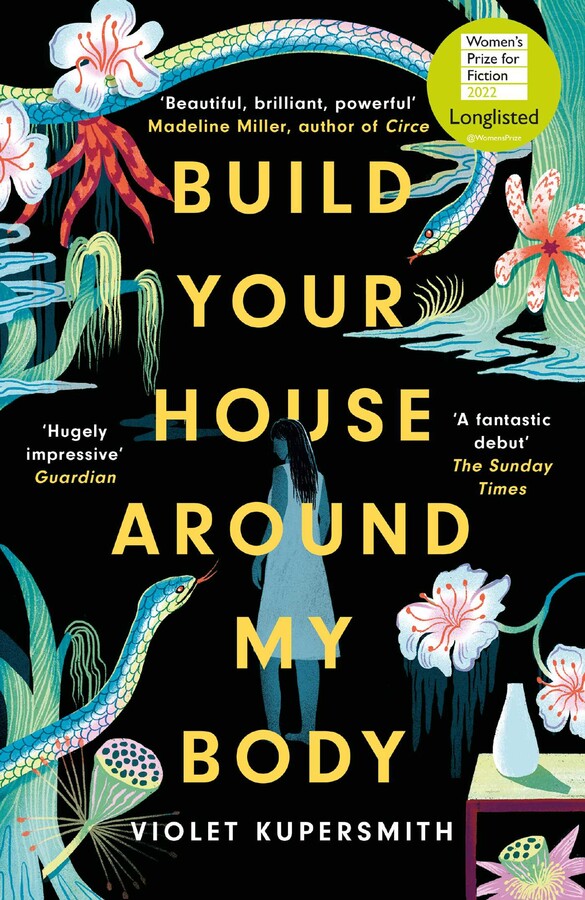

Muddy Ambiguities (Australian Book Review)

Kupersmith’s exploration of the complex relationship the Vietnamese diaspora have with the homeland is both welcome and intriguing.

Conflicted Feelings (The Griffith Review)

In a busy room at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, an unusual canvas piques the interest of many.

Gambling Research bankrolled by the gambling industry? That’s a problem (Crikey)

University of Sydney’s new gambling research centre is funded by ‘generous’ gaming companies, compromising its research - no matter the spin.

Thai Linh (COLORS X EDITORIAL| VIETNAM)

Hanoi-based artist Thai Linh appropriates the past to imagine Vietnam’s technological future.

The House of Youssef by Yumna Kassab (Mascara Literary Review)

Perhaps the truth is, sometimes we simply can’t stay afloat and we can’t keep the plane in the air—but we can create something meaningful from the wreckage.

Strangers on Country (Kill Your Darlings)

What does it mean to travel as an Asian Australian on Aboriginal land?

Arrangements /ə’reɪn(d)ʒm(ə)nts/ (BLEED/Running Dog)

At home afterwards, I listen to those variations over and over again. Then slowly, ever so slowly, I realise that this is what it means to be part of a diaspora: perhaps we are all simply arrangements of sounds from elsewhere, composed long ago.

Coming of age in Cabramatta (Sydney Review of Books)

The Coconut Children is novel that will resonate with many of us who grew here in Australia. It’s a deeply spiritual contribution to the ongoing conversation between the past and the present, the dead and the living.

The late-night meal in Ho Chi Minh City that inspired a Bankstown cafe's key dish

The meal inspired 'District 3 pasta', one of the signature dishes at Kinx Café in Bankstown.

Bringing up a bilingual child (ABC News)

Bringing up a bilingual child is hard work. But passing on your mother language is a gift beyond words

A mythical country (State Library of NSW)

As compelling as these artworks are to me, the truth is I can’t help feeling an enormous sense of loss when I look at them.

Larpb padt sandwich (Fields & Stations)

This is not a sandwich that’s been toned down for the farang palate: it demands an embrace of a new world way of eating.

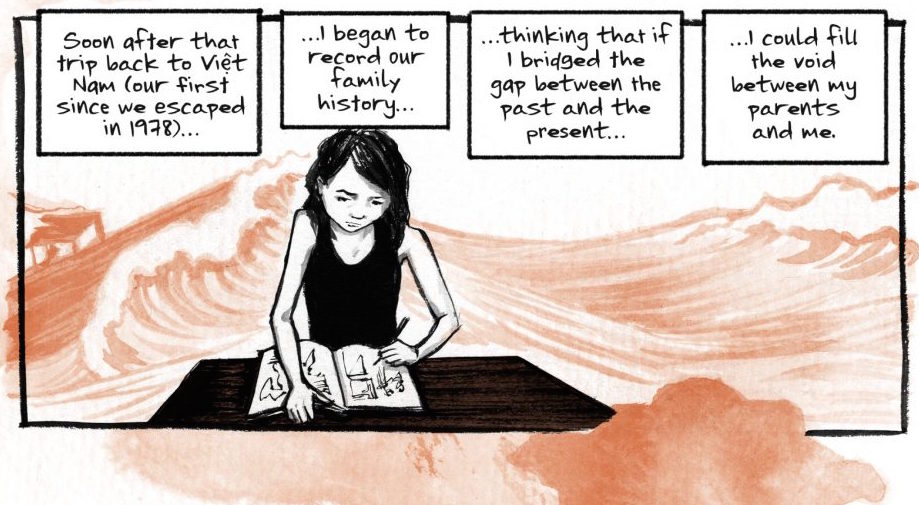

An act of recovery: Comics from the Vietnamese diaspora (diaCRITICS)

The absence of photographs in many of our lives is why comics feel like an act of recovery, with images created from memory, imagination, and reportage—to fill in the gaps.

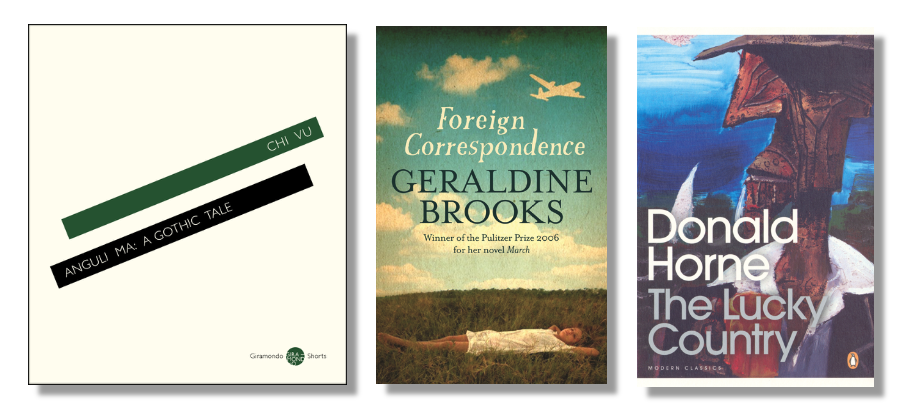

Australia in three books (Meanjin)

Growing up I struggled to maintain much interest in ‘Australian culture’—whatever that was—let alone aspiring to be involved with it.

My Junot Díaz Problem (Meanjin)

At the time Zinzi Clemmons was confronting Junot Díaz at the Sydney Writers’ Festival about his past mistreatment of her, I was elsewhere in the same building attending a writing workshop on literary nonfiction.

Welcome to the neighbourhood (New York Times)

After enduring the struggle to buy a home, a multicultural crowd of friends gathers for a Hindu celebration.

Learning through their stories (New York Times)

Project type

The enduring tradition of the famous Portuguese egg tart (Roads & Kingdoms)

The tart’s sticky sweetness fills my mouth. It may have originated in a distant place on the Iberian Peninsula, but in Dili, the pastel da nata is as everyday as bread.